We all have quirks: the way we hike up our pants, the way we frequently forget the third button, the way we inspect some delicacy we’re eating as if to reveal the true mysteries of yumminess.

I have a few quirks of my own (all of the above and about a thousand more). Here’s another: sometimes, I don’t remove the tags. Case in point, I finally banished a threadbare wool vest to Goodwill and I had to remove the tag before I chucked it in the bin. I’ve had the thing since 1997. Here’s another: I have ties which I wear on the regular, and when I do, I have to tuck away their tags so they don’t peek out.

Why don’t I just cut the damn things off?

Ah, Three-Years-Ago-Me. So young and so foolish.

Three years ago, in the final days before I turned 40, I drew a three part comic-strip, sending off my 30s. I borrowed imagery from the sequel to Madeline L’Engel’s A Wrinkle In Time, called A Wind in the Door. Like the main character in the book, I was at the epicenter of a battle between two forces: one force pressing backwards, wanting to remain zippy, unrooted, and uncommitted. The other force pressed me onwards to evolve, to put down roots. In Madeline L’Engels’s book, putting down roots is necessary for the organism’s survival. So too with me. None of my backwards-looking had to do with who I was in a marriage-bound relationship with (the best person ever) or whether I was actually happy where I was going (very much so). All of it had to do with my irrational, age-old desire to “keep the tags on.”

Like insecticide and fungicide, the “cide” in “decide” means to kill something. In this case, killing options, killing the past. And for many people, myself included, that’s scary, even when the old options aren’t actually desired. In my case, I was thrilled to be moving forward in my life with Gabi, but hosing down my “carefree 30s” with fungicide presented certain irrational challenges.

No surprise, I’ve been thrilled with how I’ve melted into my 40s. And I love being rooted and married. And yet, with the birth of my daughter, my issue with tags has crept up in some funny ways.

As Gabi and I prepared for our baby’s day of birth, I was keenly aware of the fact that one of the only truly permanent changes in life was barrelling my way. I would soon be a Dad, and there was no undoing that. Once the baby was born, (a moment Gabi and I described as stepping into a time machine), in an instant, I knew I’d become something I’d always wanted to be. My roots would be forever sunk into the soil of my very much committed future.

I believe that we can not vanquish the ghosts from our pasts, for once and for all. That’s neither a realistic nor a healthy way to grow and evolve. Rather, we find ways to put these ghosts in their places. In my case, I will continue to choose to allow Life to sweep me forward and find adaptive ways to let my quirk express itself. I’m still me. I don’t want to go backwards. But I haven’t stopped craving ways of keeping things unknown, unwritten, unrevealed, and mysterious – even (or especially) as my future comes into focus — as I make better and better friends with permanency.

Two important tags: A) the little plastic clamp that pinched my daughter’s lifeline from the Mother-Ship. B) the tag from the backpack Gabi and I used to bring our gear to the hospital. My mother-in-law made me cut the tag.

The first quirk of post-birth tag-preservation came in the form of my daughter’s umbilical stump. After I cut the cord, moments after my daughter emerged into this world, a tiny plastic clamp pinched her lifeline to her 9 month lifeboat. In a week, my wife and I were told, the stump of tissue would fall off. Which lead me to an obvious and pressing question.

Q: What does one do with the ultimate tag of a human life?

A: We’re not sure. Some day, Gabi and I may bury it, perhaps as part of a ritual of our own design.

The second tag comes in the form of a name. The day after the baby’s birth, I held in my hand an official-looking piece of paper, instructing me to print my new baby’s name in block letters. In an ancient and familiar way, I hesitated to put pen to paper. I procrastinated from hour to hour and day to day. There seemed to be no perfect moment to make a mark that will last forever.

Eventually, I did. One quiet hour, I wrote the baby’s name, and handed the clipboard over to a clerk who brought that little swash of ink into eternity. Eight days later, at a Jewish naming ceremony, my daughter’s name was revealed to all the world.

Her English name was decided upon, declared to all. As for her Hebrew name, there’s a catch. Her Hebrew name, Malka, means “Queen.” And though it’s customary to give babies a hyphenated Hebrew name, Gabi and I decided not to pick her second Hebrew name. One day, Anna will decide, for herself, what she aspires to be the Queen of.

Let the past be the past. Let the future be unknown. And when the time is right, let Anna Mari cut off her own tag.

This is a noteworthy time to be born a girl in America. Lots of us are angry about the messages that our leaders and our media send out about what a woman is and what a woman isn’t. The reality is that, in the company of other strong women, and in solidarity with men who want the world to be a better place, you will raise your own fist/sign/flag against the system that probably will still be suggesting that you’re the other-gender. You won’t do this alone. At some point, not long from now, your mother will take a picture of you at a march or a protest. You’ll be surrounded by countless others, fighting for the same change. You’ll be sitting on my shoulders.

This is a noteworthy time to be born a girl in America. Lots of us are angry about the messages that our leaders and our media send out about what a woman is and what a woman isn’t. The reality is that, in the company of other strong women, and in solidarity with men who want the world to be a better place, you will raise your own fist/sign/flag against the system that probably will still be suggesting that you’re the other-gender. You won’t do this alone. At some point, not long from now, your mother will take a picture of you at a march or a protest. You’ll be surrounded by countless others, fighting for the same change. You’ll be sitting on my shoulders.

Go out into the world. Or go back to bed.

Go out into the world. Or go back to bed.

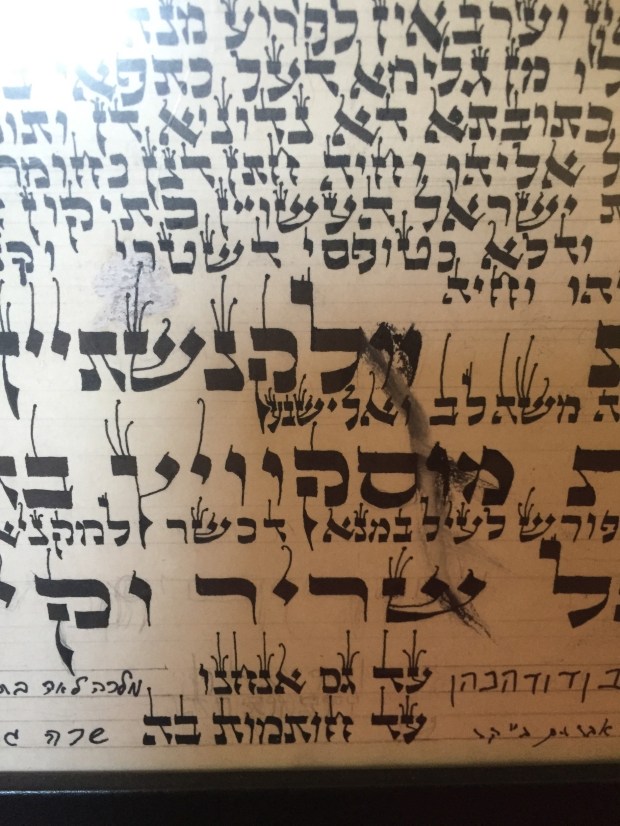

My favorite: as I mentioned earlier, I hand calligraphed (yes, that’s a word) the traditional Hebrew marriage contract. It took about four months. I started over at least ten times, for errors as small as a smudged letter or a dimple in the paper. Towards the ketubah’s completion, a stray greasy onion got stuck on the parchment. An alchemical combination of cornstarch and white ink masked the stain, and from that point on, I treated the contract as if it were a priceless fragment of the Dead-Sea Scrolls. It stayed in a protective sleeve between two pieces of pristine parchment.

My favorite: as I mentioned earlier, I hand calligraphed (yes, that’s a word) the traditional Hebrew marriage contract. It took about four months. I started over at least ten times, for errors as small as a smudged letter or a dimple in the paper. Towards the ketubah’s completion, a stray greasy onion got stuck on the parchment. An alchemical combination of cornstarch and white ink masked the stain, and from that point on, I treated the contract as if it were a priceless fragment of the Dead-Sea Scrolls. It stayed in a protective sleeve between two pieces of pristine parchment.

A Chassidic Story.

A Chassidic Story.

We returned to my cousin’s house to shower and freshen up for dinner, and standing in the living room in my towel, sipping coffee and watching the afternoon wind whip through the palm trees, I felt like a prince.

We returned to my cousin’s house to shower and freshen up for dinner, and standing in the living room in my towel, sipping coffee and watching the afternoon wind whip through the palm trees, I felt like a prince. What have I accomplished a hundred times?

What have I accomplished a hundred times?

Let’s image the Snappy Answers scenario, but swap out the nurse. Instead, it’s you and a person you know well. Someone who was once a friend. A family member who’s made you miserable many times. A colleague who has turned work into hell. And let’s say this conversation will have no consequences, no chance of going kablooey. It takes place in a bubble. A Bubble Conversation. Perhaps you’ve fantasized about this: saying the thing you’ve always wanted to say? Force him to confront reality — what you really think of him. Demand her to face your charges — without escape, without the chance to twist it against you.

Let’s image the Snappy Answers scenario, but swap out the nurse. Instead, it’s you and a person you know well. Someone who was once a friend. A family member who’s made you miserable many times. A colleague who has turned work into hell. And let’s say this conversation will have no consequences, no chance of going kablooey. It takes place in a bubble. A Bubble Conversation. Perhaps you’ve fantasized about this: saying the thing you’ve always wanted to say? Force him to confront reality — what you really think of him. Demand her to face your charges — without escape, without the chance to twist it against you.

That evening, a wise friend asked: is there anything you can learn from this? After refusing to even consider the possibility, I hunkered down and admitted a few things. As the trolls remarked, I do have a big, bushy

That evening, a wise friend asked: is there anything you can learn from this? After refusing to even consider the possibility, I hunkered down and admitted a few things. As the trolls remarked, I do have a big, bushy

Twenty-whatever years later, it took a trip down memory lane to recall my teenage evolution: from freshman hallway-cringer to senior

Twenty-whatever years later, it took a trip down memory lane to recall my teenage evolution: from freshman hallway-cringer to senior

As an adult, I’ve made peace with License to Ill (it’s an AWESOME album), and with trends of all sorts. It helps that, as I went through my twenties and thirties, fitting in via the

As an adult, I’ve made peace with License to Ill (it’s an AWESOME album), and with trends of all sorts. It helps that, as I went through my twenties and thirties, fitting in via the  Behind the scenes, fitting in with your world is more than putting on a confident face and striding into a room like you own the place. It’s also about how you present yourself. How you “read.” And if you don’t think that’s true, consider the reoccurring dream where you’re naked in front of an audience. Oh, you know that dream? Exactly: everyone feels, to some degree, unclothed – vulnerable – with our doubts and anxieties. We do our best to dress ourselves, metaphorically, with confidence. And we can wear actual clothes, hopefully with confidence, every day.

Behind the scenes, fitting in with your world is more than putting on a confident face and striding into a room like you own the place. It’s also about how you present yourself. How you “read.” And if you don’t think that’s true, consider the reoccurring dream where you’re naked in front of an audience. Oh, you know that dream? Exactly: everyone feels, to some degree, unclothed – vulnerable – with our doubts and anxieties. We do our best to dress ourselves, metaphorically, with confidence. And we can wear actual clothes, hopefully with confidence, every day.