Every year, the Jewish holiday Yom Kippur comes around and gives us the opportunity to apologize to people we have harmed. For those of us who observe Yom Kippur, it forces us to think deeply about the ups and downs of interpersonal repair. For those of us who don’t celebrate Yom Kippur, it can be like being in Las Vegas during a NASCAR championship: you can enjoy the experience vicariously. Just swap out hordes of NASCAR fans and exhaust fumes for ornery, hypoglycemic Jews.

Every year, the Jewish holiday Yom Kippur comes around and gives us the opportunity to apologize to people we have harmed. For those of us who observe Yom Kippur, it forces us to think deeply about the ups and downs of interpersonal repair. For those of us who don’t celebrate Yom Kippur, it can be like being in Las Vegas during a NASCAR championship: you can enjoy the experience vicariously. Just swap out hordes of NASCAR fans and exhaust fumes for ornery, hypoglycemic Jews.

Teshuva is the main thing we Yom Kippur enthusiasts do on the 10th day of the Jewish month of Tishrei. Teshuva is usually translated as “repentance,”(though yuck – I hate that word). And every year, I hear someone quote the medieval Spanish Rabbi Moshe Ben Maimon’s formula for “doing teshuva.”

Step 1: Admit how you effed up. (Mishneh Torah 1:1).

Step 2: Show that you’re sorry, and take whatever actions you need to make sure you don’t eff up again. (Mishneh Torah 2:2) and fix whatever damage you’ve caused (Mishneh Torah 2:9).

Step 3: Don’t eff up again if you’re ever in the same position in the future. (Mishneh Torah 2:1).

On the one hand, this is great stuff. I wish people did this more often. I should do this more often.

On the other hand, the simplicity of these steps reminds me a bit of “Dick in a Box.” Step 1, Step 2, Step 3, and “That’s the way you doooo it.”

The Dick-in-a-Box Sorry System is great for situations where the “wrong” is totally clear: for any version of stepping on someone’s foot.

The Dick-in-a-Box Sorry System is great for situations where the “wrong” is totally clear: for any version of stepping on someone’s foot.

“One. I’m sorry I stepped on your foot. Two. I will keep an eye out for your feet. Three. Here’s a new pair of shoes. Teshuva! That’s the way you doooo it.”

And being married, I see that daily “teshuva” is an integral part of sharing a home and a life with someone. Through teshuva, I have learned to close the cabinet doors, to clean the cat’s litter box without being asked to, and to communicate when I will be home later than I’d expected.

And if we’re lucky, that type of apologizing is good for, say, 95% of the conflicts that arise in a given year, whether at home or at work or with friends. But for that other 5%, Yom Kippur forces us to confront the fact that any real conflict – certainly one which has lingered in our minds for months – is likely to be the result of a messed up relationship system. And when the relationship is effed up, “apologizing for harm” and “promising not to do it again” strikes me as a serious oversimplification. And any approach to a complex problem with an over-simplified solution will be disappointing. Sometimes dangerous.

An example: someone has mistreated you regularly. Then they come to you and ask for forgiveness for “any time they might have harmed you.” Their Dick-in-a-Box apology doesn’t allow for you to express the fact that the relationship is unbalanced and toxic. It puts you in a situation of disempowerment, like those awkward scenes in rom-coms where the evil Alpha Male, astride a white horse, “asks” the female lead to marry him while the whole kingdom (and his armed guards) watch; she has no real agency. And Yom Kippur lurking around the corner adds that whole “kingdom watching” element. It’s not fair.

Forgiveness is not a right. And an apology is not sufficient.

The flip side, though, is also true: when apologizing to someone, never simply apologize for “anything you might have done” (gah!) and don’t just name the thing (“I’m sorry for stepping on your shoes”).

Rather: and here’s the toughest thing of all. If you want to apologize, approach someone with the desire to make things better, and ask if they’d like to speak first. Don’t see it as an opportunity to harvest an apology–see it as the chance to learn something.

We don’t live in a world of sin and repentance; rather, we live in a world of complex, competing needs with many, many unfortunate consequences as we try to meet our needs. For those of us who are celebrating Yom Kippur tomorrow night, and for those of us who are not, may we choose our approach to apologies not with a goal in mind, but with the desire to understand. With the willingness to be told the Truth.

And that’s the way you dooooo it.

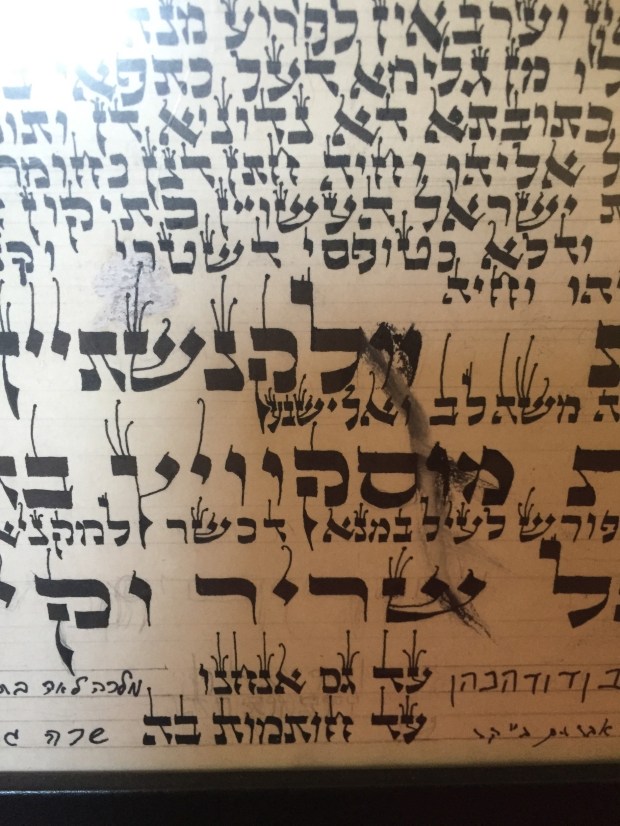

My favorite: as I mentioned earlier, I hand calligraphed (yes, that’s a word) the traditional Hebrew marriage contract. It took about four months. I started over at least ten times, for errors as small as a smudged letter or a dimple in the paper. Towards the ketubah’s completion, a stray greasy onion got stuck on the parchment. An alchemical combination of cornstarch and white ink masked the stain, and from that point on, I treated the contract as if it were a priceless fragment of the Dead-Sea Scrolls. It stayed in a protective sleeve between two pieces of pristine parchment.

My favorite: as I mentioned earlier, I hand calligraphed (yes, that’s a word) the traditional Hebrew marriage contract. It took about four months. I started over at least ten times, for errors as small as a smudged letter or a dimple in the paper. Towards the ketubah’s completion, a stray greasy onion got stuck on the parchment. An alchemical combination of cornstarch and white ink masked the stain, and from that point on, I treated the contract as if it were a priceless fragment of the Dead-Sea Scrolls. It stayed in a protective sleeve between two pieces of pristine parchment.

A Chassidic Story.

A Chassidic Story.

We returned to my cousin’s house to shower and freshen up for dinner, and standing in the living room in my towel, sipping coffee and watching the afternoon wind whip through the palm trees, I felt like a prince.

We returned to my cousin’s house to shower and freshen up for dinner, and standing in the living room in my towel, sipping coffee and watching the afternoon wind whip through the palm trees, I felt like a prince. What have I accomplished a hundred times?

What have I accomplished a hundred times?

Let’s image the Snappy Answers scenario, but swap out the nurse. Instead, it’s you and a person you know well. Someone who was once a friend. A family member who’s made you miserable many times. A colleague who has turned work into hell. And let’s say this conversation will have no consequences, no chance of going kablooey. It takes place in a bubble. A Bubble Conversation. Perhaps you’ve fantasized about this: saying the thing you’ve always wanted to say? Force him to confront reality — what you really think of him. Demand her to face your charges — without escape, without the chance to twist it against you.

Let’s image the Snappy Answers scenario, but swap out the nurse. Instead, it’s you and a person you know well. Someone who was once a friend. A family member who’s made you miserable many times. A colleague who has turned work into hell. And let’s say this conversation will have no consequences, no chance of going kablooey. It takes place in a bubble. A Bubble Conversation. Perhaps you’ve fantasized about this: saying the thing you’ve always wanted to say? Force him to confront reality — what you really think of him. Demand her to face your charges — without escape, without the chance to twist it against you.

That evening, a wise friend asked: is there anything you can learn from this? After refusing to even consider the possibility, I hunkered down and admitted a few things. As the trolls remarked, I do have a big, bushy

That evening, a wise friend asked: is there anything you can learn from this? After refusing to even consider the possibility, I hunkered down and admitted a few things. As the trolls remarked, I do have a big, bushy

Twenty-whatever years later, it took a trip down memory lane to recall my teenage evolution: from freshman hallway-cringer to senior

Twenty-whatever years later, it took a trip down memory lane to recall my teenage evolution: from freshman hallway-cringer to senior

As an adult, I’ve made peace with License to Ill (it’s an AWESOME album), and with trends of all sorts. It helps that, as I went through my twenties and thirties, fitting in via the

As an adult, I’ve made peace with License to Ill (it’s an AWESOME album), and with trends of all sorts. It helps that, as I went through my twenties and thirties, fitting in via the  Behind the scenes, fitting in with your world is more than putting on a confident face and striding into a room like you own the place. It’s also about how you present yourself. How you “read.” And if you don’t think that’s true, consider the reoccurring dream where you’re naked in front of an audience. Oh, you know that dream? Exactly: everyone feels, to some degree, unclothed – vulnerable – with our doubts and anxieties. We do our best to dress ourselves, metaphorically, with confidence. And we can wear actual clothes, hopefully with confidence, every day.

Behind the scenes, fitting in with your world is more than putting on a confident face and striding into a room like you own the place. It’s also about how you present yourself. How you “read.” And if you don’t think that’s true, consider the reoccurring dream where you’re naked in front of an audience. Oh, you know that dream? Exactly: everyone feels, to some degree, unclothed – vulnerable – with our doubts and anxieties. We do our best to dress ourselves, metaphorically, with confidence. And we can wear actual clothes, hopefully with confidence, every day.

Here’s an embarrassing story.

Here’s an embarrassing story.